Fix Climate Action 1: Why Many Cities Fail to Act

A federal "municipal climate action program" could overcome an important barrier holding cities back from taking climate action.

Some Canadian cities are moving forward with ambitious climate plans. David Miller’s Solved: How the World’s Great Cities are Fixing the Climate Crisis notes Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal as three Canadian municipalities showing leadership with different types of climate action.

But many other Canadian cities are not taking action on climate. Even the cities that have prepared climate action plans.

Understanding inaction

There are a lot of reasons cities might not be taking action, including City Councils that:

Don’t have a climate plan

Deny action is necessary, or don’t believe their contribution is meaningful

See the costs of a climate plan, but don’t understand the benefits

Are culturally opposed to the sustainable transportation and renewable energy measures that need to be taken

And there may be another reason. Municipal accounting practices.

Let’s dig into this by looking at one city’s climate plan.

City of Ottawa’s climate plan

Our sister publication, the 613, has spent a lot of time deep in the numbers of the City of Ottawa’s Energy Evolution plan. That is a plan to get emissions to net zero by 2040 for City Hall and 2050 for the broader community.

In the case of Ottawa, “community” emissions from households, businesses and other organizations account for 96% of total emissions. “Corporate” emissions from City Hall operations account for 4%.

For Ottawa, climate action could be a fiscal win for a city, and for its municipal finances.

It comes with a price tag of $32 billion by both City Hall and the wider community. What critics overlook is that the transition leads to energy savings and new revenues of $44 billion. In other words, implementing the Energy Evolution climate plan would net the region of Ottawa $12 billion over 30 years.

Spending and savings for City Hall

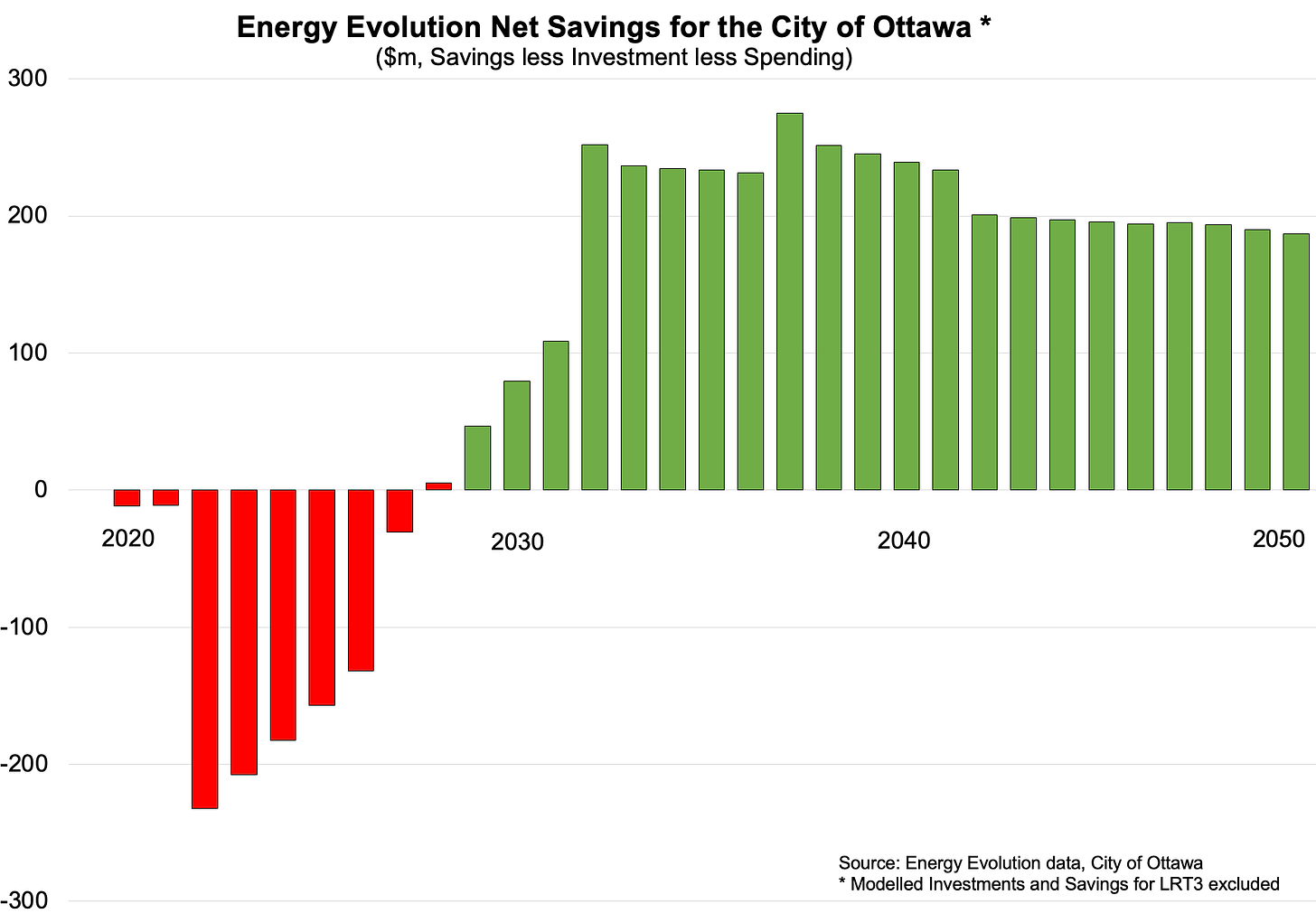

When we look at the actions specifically required by City Hall, we see a mismatch between when taxpayers spend and when taxpayers save. As per the chart below, taxpayers would invest over the first decade, and then reap the benefits over the following two decades. (Note: this data is a few years out of date now, but it still directionally correct in portraying the pattern of climate spending and saving for City Hall.)

That is an attractive return on investment. So why hasn’t City Council moved forward?

Because “short term pain for long term gain” doesn’t work well in a 4-year election cycle. A City would need to take significant spending decisions today that would have little direct payoff during this term of Council.

Cash vs accrual accounting

And the accounting practices that cities use compound this problem.

Cities in North America use “cash accounting” — managing the books on a cash in, cash out basis. The federal and provincial governments use “accrual accounting”. Accrual matches revenues with expenses at the time of the transaction, rather than when payments take place. The cost of investments gets amortized over time and matched against lifetime revenues.

We’ve talked previously about the impact of cash and accrual accounting in the context of housing, and the same logic applies to climate action. A government using accrual accounting can match expenditures with revenues, effectively realizing those future revenues and savings when expenses are made.

But since municipal governments don’t use accrual accounting, this matching is not directly available to them.

Enter the feds

The federal government has a number of support programs (beyond carbon pricing) for transitioning different groups and industrial sectors to a clean future. Switching to electric vehicles. Retrofitting homes and buildings. Supporting provinces, territories and indigenous communities. Reducing oil and gas emission intensity. Expanding renewal electricity. Supporting farmers. And more.

But the federal government doesn’t have much in the way of support to municipalities. Federal support could be as simple as a loan program — making low-cost financing available to municipalities for climate action, which are repaid through future energy savings and new revenues.

In an accrual accounting world, a loan program would be a very low fiscal cost to the federal government.

The Canada Infrastructure Bank already provides this sort of financing for electric buses — in which municipalities borrow the money now and pay back the loans with future fuel and maintenance savings.

The feds could scale up that CIB approach — making loans available to municipalities to:

Upgrade their municipal fleets

Retrofit municipal buildings

Transform waste emissions and wastewater heat into energy sources

Invest in active transportation and transit networks

Financial solutions

Transitioning to a low carbon future can be a fiscal win for municipalities. But accounting practices make that action onerous for current City Councils.

The federal government could create help solve the mismatch between when taxpayers spend on climate action and when they save. We are suggesting that the federal government consider creating a “municipal climate action program”, with loans to cities that allow for upfront investments, and with loans repaid from future cost savings.

The federal government supports many other groups and industrial sectors across Canada in undertaking climate action. It’s time to extend that support directly to cities.

this is a very useful take on what ails our decision making .. incl. both the inability of politicians to look beyond their term office ( ie. somewhat understandably )... and the way we account for what we do as taxpayers / voters; it seems to need a serious legislative rethink and change, but this one shot / ie. take on things at this point moves the needle ... if only to get that level of understanding required before we try to move to change things. Progressive politicians themselves could assist in making this happen.